- Home

- Michael Calvin

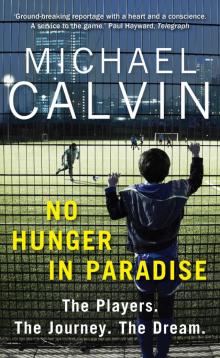

No Hunger In Paradise Page 11

No Hunger In Paradise Read online

Page 11

‘The boy, Lauren, was ruining my training session. His parents had split up. He was on drugs, robbing cars, the lot. I told him I could help him become a man, but he had to play ball with me. The kid had never heard this before. When I said I wanted to help him get somewhere in life I could tell he was looking at me, thinking, what’s in it for him?

‘Most people would have ditched him, chucked him out. But we persevered. The way that kid turned himself around, through the discipline he learned and the direction he gained through football, was unbelievable. I saw him recently. He is in the army and he told me, “You changed my life.” This isn’t about me, and football isn’t necessarily about making a living. It can be about making a life.’

On the page, stripped of the emotion with which they are delivered, those words can appear bland, bloodless, even calculating. But try telling that to those, like Linley, who have seen what happens when latent powers are released or, more damningly, suppressed:

‘The best thing about doing what I do is seeing a boy go out there and become the person he was six months previously. He understands he has someone behind him, and that he is not doing it on his own. Out there on the academy field coaches are just looking at the one boy they think is going to make it. The others are just numbers. To me, every boy is the same. It doesn’t matter whether he is playing for Manchester United or Soham Town Rangers.

‘The worst thing about this job is a boy having all the ability in the world, and we can’t turn him around because he is too far gone. He is ruined and walks away from it. He will wake up in ten years’ time and regret what he has done. There’s a lot out there like that. Often it is one little setback that changes their life.’

He pauses when I ask him to delve deeper, and expand on those moments when he despairs of the sport in which he operates. He takes the path less travelled, and provides me with a name: Kieran Bywater.

7

A Parent’s Warning

EVERYONE HAS THEIR breaking point. Kieran Bywater reached his on a nondescript park pitch in Buckhurst Hill, fifteen minutes into a match designed to showcase his talent and renew his ambition. He stopped suddenly, and walked slowly around the touchline. At the moment of submission, behind one goal, he sank to his knees, clutched his head in his hands, and wept.

‘What am I doing here?’ he asked those, like Mike Linley, who instinctively came to his aid. ‘A couple of weeks ago I was playing against PSV Eindhoven. Now look at me. I can’t do this.’ He was inconsolable, and led to the sanctuary of the car park by his father, Simon. In professional football, no one likes to be around to hear you scream.

Rejection by West Ham, in unexpected circumstances, had the deadly efficiency of a depth charge. It took time for its percussive force to be fully felt, since Kieran was sufficiently well regarded, as a high-scoring midfield player with leadership qualities and first-team potential, for Manchester United, Norwich City and Aston Villa to register an initial interest.

He underwent a series of trials, at Villa, Coventry and Sheffield United. He spent a week at Crewe Alexandra, who had a change of heart and signed two older players at his expense. Mark Robins, Scunthorpe’s manager at the time, delayed his decision until after the summer break. Kieran’s best experience was a five-week spell at Manchester United under Warren Joyce, head coach of United’s second team before he left to manage Wigan Athletic.

Joyce recommended him to Barnsley, but as an under-21 player, requiring a salary and the security of a contract, he was not as attractive a proposition as a loanee of similar age, whose parent club were willing to underwrite his wages. Villa’s under-21 coaches, Gordon Cowans and Stuart Taylor, were impressed, but the political dynamics of the academy ensured priority was given to promoting from the under-18 group.

The new reality became unavoidable during an invitational trial for Cambridge United, undertaken because of its proximity to the family home in Sawtry, a village eight miles north of Huntingdon. The dressing room was full of familiar figures, second-year scholars and first-contract pros released from Premier League clubs. Mutual expressions of surprise that they should share such a fate were placed into brutal perspective when none were offered a contract by the League Two club, or even an extended examination.

The first four stages of grief, in a football sense, are denial, anger, fearfulness and depression. The fifth involves defiance, in those determined to pursue an increasingly distant dream, or acceptance, in those who let it go, and realign their life. That final step involves a deeply personal, uniquely painful, decision. Though taken in isolation, its impact is felt by those who share the journey.

Simon Bywater’s response to his son’s plight was to post an article on his LinkedIn account entitled ‘A parent’s warning – football academies’. It was a 3,156-word cri de coeur, designed ‘to highlight a side of football only a few see and even less talk about’. It began with a simple statement: ‘I can’t sit back and bite my tongue any longer.’ It touched a nerve, and quickly went viral on social media.

A poignant study of devotion in adversity, his story was driven by a series of deeper truths. These were put into context by Simon’s description of bringing his son up to aspire to the ten defining values of the Royal Marine commandos, with whom he served in Iraq in the first Gulf War: courage, unity, determination, adaptability, unselfishness, humility, cheerfulness, professionalism, fortitude and humour.

Football’s contrasting culture took little time in manifesting itself once Kieran signed for West Ham at 9. According to Simon, the club circumvented prevailing travel rules by offering to register Kieran at a local address instead of his home, which was outside the one-hour time limit for players under the age of 13. It cost £400 a month in fuel to ferry him to training and matches. Invariably, he did not return from training until 11 p.m. on school nights; homework in the car was virtually impossible in the winter darkness.

‘How could I turn around and say, “No, you can’t go any more?”’ Simon wrote.

‘It would have broken his heart as an eleven-year-old and, given our location in the country, where else could he have gone for his football, as West Ham would have sought compensation? So in effect we were caught in a catch-22 situation over his registration if he wanted to leave.

‘Family life begins to revolve around the club. As a parent, school holidays are full of football tournaments and games. You have to be prepared to arrange things at minimal notice. Dropping family events is the norm. The sacrifices as a family will be unseen by most and certainly ignored by the club. With hindsight we were naïve but like many we couldn’t see it.’

Despite the difficulties, Kieran progressed rapidly, regularly playing up an age group. At 13 he moved into a club house in Romford from Wednesday to Saturday. The family funded a maths tutor to support his preparation for his GCSEs. By 16, when he was offered a two-year scholarship and the guarantee of a subsequent one-year professional contract, at £500 per week, he was in the ascendancy.

He chose not to have an agent, despite his parents being pestered at each home game. ‘We avoided these individuals who circled training grounds like vultures,’ Simon recorded. ‘There was a lot of pressure from agents to sign and explore avenues with other clubs. We truly didn’t have a clue who to turn to for advice and nobody spoke about it. It was as if it was some kind of a dirty conversation to have. At the time, our son wanted to remain loyal to West Ham.’

He captained the under-18s and, latterly, the under-21s. He was nominated as academy player of the year and played a behind-closed-doors first-team game at Upton Park against Queens Park Rangers. Even his most traumatic moment, laying a wreath in the centre circle at a home game in memory of his friend and housemate Dylan Tombides, who had passed away from testicular cancer, was a symbol of his status.

The replacement of the universally admired Tony Carr as academy director at the start of the 2014–15 season proved to be of pivotal personal significance. Terry Westley, Carr’s successor, had worked with West

Ham’s powerbrokers, David Sullivan, David Gold and Karren Brady, at Birmingham, where he restructured the academy and instigated such innovations as joint training sessions with Aston Villa and West Bromwich Albion.

While at St Andrew’s, he was one of six club representatives responsible for drawing up the Elite Player Performance Plan. He subsequently became the Premier League’s head of professional development, a position from which he was able to dispense the informal patronage that is rarely forgotten in football’s cloistered world. Regime change at a football club is invariably brutal. It is an accepted part of life at senior level, but a relatively new phenomenon at junior level. Westley had a clear brief to impose change at West Ham, which was to lead to the departure of two of Kieran’s previously influential supporters, senior development coaches Trevor Bumstead and Nick Haycock.

According to Simon Bywater, Westley was initially supportive of his son. He praised his goal-scoring record, and seemed concerned that Kieran had only a year left on his contract. In December 2014 Kieran represented the club at a function celebrating the Bobby Moore Foundation at the Grosvenor House hotel. His father reflected that ‘there was no indication that he would be leaving the club or hadn’t been performing’.

He confirmed his son’s contract status, at Westley’s request, when they met at a game against Cambridge United. Soon afterwards, in a meeting in the academy director’s office, Kieran verified that he had no agent. According to his father, Westley advised Kieran that he would find a representative for him, and extend his contract for a further two years. In January 2015, Westley called Kieran into his office and informed him he was free to leave the club. He claimed he wanted to keep him, but had been overruled by Sam Allardyce, the club’s first-team manager at the time. ‘Who could we believe and where did our son stand in all of this?’ Simon wrote. ‘He was devastated and once outside the office door cried his eyes out. Our phone didn’t stop ringing from people stating they had heard the news and couldn’t believe it. All the clichés came out, “One door closes another one opens.” “He will have no problem finding a club and be snapped up.” “They have made a huge mistake.” Privately, this didn’t ease any of the pain for him.

‘So why this article? I want to warn other parents going down the academy football route. You will hear so much storytelling and false promises. Trust nothing you are told and always have a plan B outside football. Clubs will say one thing but do something completely different. One minute you’re top dog, the next you’re bottom of the pile and your son could become very isolated overnight for no apparent reason.

‘Some will think I’m a bitter dad because our son didn’t get an opportunity at West Ham. That’s not the case. What I’m bothered about here is the way clubs conduct themselves during the academy process. I say this because I was recently on the touchline in the Midlands, at an under-21 trial game. I spoke to parents of lads from Villa, Chelsea, Fulham and Arsenal to name a few. They all had similar stories to tell, young lads facing the depression of isolation having given everything to a club from the ages of seven, eight or nine.’

Simon Bywater’s clarion call for an improvement in the game’s duty of care to young players had potentially far-reaching consequences. His background as a former detective, dealing with gangland murder cases involving teenagers with MAC-10 machine guns, and his current practice, as a private investigator, enabled him to retain perspective when the club threatened legal action. The miscellany of the dispute, carefully annotated files and indexed statements, is spread out before him, on a well-polished walnut dining table in a neat house that occupies the corner plot in a modern cul-de-sac. A small white dog has been indulged before being ushered into the adjoining kitchen.

He speaks of the ‘horrendous’ experience of being branded a liar, the unsolved mystery of how and why his LinkedIn account was hacked and various items deleted. To be clear, West Ham and Westley deny all knowledge of, or involvement in, this. Simon maintained his comments were in the public interest, and argued the article could not, as was suggested, have harmed Westley’s reputation, since he was given a new five-year contract, as Academy Manager and Head of Coaching and Player Development, two weeks after it was published.

‘I’m used to dealing with lawyers because of my job, but if I was your run-of-the-mill parent I would have potentially panicked, submitted, rolled over and had my tummy tickled by them. Don’t get me wrong. I felt alone, the only one prepared to put his head above the parapet. I had sleepless nights over it because they were just trying to bully me. I’m an ordinary bloke who earns an average living and they are a multi-million-pound business, but I could see the bigger picture here.’

That picture is given sharp focus by one of the ring-bound folders, which contains email printouts and handwritten notes. A vicar promises pastoral support. A father asks for advice because his 7-year-old son is being pursued by a posse of clubs led by Arsenal and Newcastle. Correspondence features senior players who identify with Kieran’s setback, and parents who are close to despair.

One parent writes: ‘Our son is quite frankly being treated awfully. He has suffered so much at the hands of his academy, both educationally and psychologically, due to the underhand tactics going on. Your article resonates with my wife and I, as parents. You are so correct when you say that people outside just don’t realise the stress it causes the whole family.’

The dossier includes the testimony of a League Two player, driven to share his fate at the hands of a new academy director at his first club: ‘He came in and started slating everything. There wasn’t a player in the building, and the academy wasn’t good enough, which was a load of rubbish. Not many people realise this but what that does is buy him some time in his job. It lets him get his feet under the table and takes the pressure off him.

‘He then brings in his own players, from his previous clubs, and starts scouting around elsewhere for players who he signs, and puts a clause in [their contracts which states], that if those players play in the first team, he gets a bonus. The way he sees it, if I played in the first team, he wouldn’t get any credit or money, because he wasn’t the man who signed me, so there isn’t anything in it for him.

‘I was top scorer in the under-18s team, I captained the reserves, and in the last year I was training with the first-team squad every day, and playing in pre-season friendlies. Everything was going fine, exactly the same as Kieran. There was no one left at the club that had been involved in my development, and I was seen as a threat. When the first-team manager changed, the academy director went to him, and I never played again.’

Objectivity is virtually impossible to sustain, since parents are understandably obsessive about the welfare of their sons, and clubs like West Ham have every right to protect and project a philosophy summed up by the ‘Be Inspired’ strapline on the playbook given to every player at the club aged from 12 to 16. Yet one admission, contained in correspondence to the Bywaters from a stranger, acts as a haunting challenge to the game itself:

‘I can’t watch football now because every time I see a young player, I think, how many casualties have there been?’

Jamie Herbert, the Premier League’s Head of Legal – Football and Regulatory Services, interviewed Simon and his son at the family home about their experiences, paying specific attention to the alleged breach of travel rules, which included suspicions of false documentation. The Bywaters refused Herbert’s request to attend a disciplinary tribunal due to a damning sense of pointlessness.

‘I said, well, what’s in it for Kieran? He’s been released by West Ham. You’ve got EPPP rules and regulations that you should be enforcing. You should be checking that information is correct when it’s submitted to the Premier League. I’m not putting Kieran in, to be cross-examined for a day. He’s not going to get anything out of it. Even if they find West Ham guilty, what are they going to do, fine them thirty grand? It’s nothing to them, is it?’

West Ham categorically deny circumventing the existing trave

l rules at the time by offering to register Kieran at a local address instead of his home. A statement also stressed: ‘Terry Westley categorically denies that he instructed Kieran to take one specific agent. It is the club’s policy to distance themselves from appointment of agents.’ The Club insists: ‘Kieran was released by West Ham because it was agreed by the senior management team that he was not the exceptional standard required to make the step up to become a professional footballer at the club.’

Simon Bywater attempted to use his experience positively, by liaising with Simon Andrews and Peter Lowe of the Players’ Trust. They lobbied the Premier League to introduce a standardised exit strategy at academy level, and suggested scholarships should be awarded at 15, rather than 16, to avoid distractions in the GCSE academic year. The Premier League responded to concerns about educational welfare by monitoring GCSE results, and comparing them to national and regional averages.

‘I joined the Marines at sixteen, so I understand that you’ve got to stand on your own two feet, but when you’re being talked to by people who you’ve looked up to, it’s very difficult to negotiate. Kieran’s exit strategy was, come in, sit down, yeah, we’ve had a chat about it, Kieran, you’re not getting a new contract.

‘If we are talking about a nationwide procedure, look at what Southampton do. They bring the player, the parent and the agent in. They have a couple of staff there, and minute the meeting. Everyone signs it, to show everyone’s happy with it. Everyone has the opportunity to contribute to the discussion. It’s not back-of-a-blinking-fag-packet stuff, see you later, mate.

‘The football industry reminds me of the BBC during the Savile era. Let’s be clear it’s nothing to do with sexual offences. It’s to do with a similar culture of everyone knowing something bad is going on, but it’s easier to keep quiet, and ignore the problem. A question might come up from a lone parent or player but they are easily muffled and quickly swept under the carpet.’

No Hunger In Paradise

No Hunger In Paradise The Nowhere Men: The Unknown Story of Football's True Talent Spotters

The Nowhere Men: The Unknown Story of Football's True Talent Spotters