- Home

- Michael Calvin

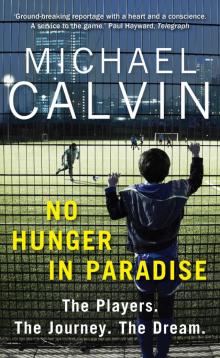

No Hunger In Paradise Page 14

No Hunger In Paradise Read online

Page 14

‘You’ve got to do a lot of work to reinforce the point they are not really on the road yet. They feel like a pro, because of the professionalism of an academy environment in which everything is just incredible, beautiful and touch screen. They think they’ve arrived and they haven’t. They’re miles away.

‘I tend to know in the first meeting if a player or a parent is for me or not. I fully expect the parents to have their say, and beyond that make major decisions. I never presume they’re going to hand their son over to me and walk away. That is not the way it should be. Sometimes, you just get the feeling that the parent isn’t going to listen to anybody anyway.

‘I walk away from the start, in a nice way. Instead of saying, “I don’t want your brat,” I usually ask who else they have spoken to, or worked with. No matter what they say, no matter which name they come up with, I tell them what a good job he would do for them. That’s the best way of handling a delicate situation.’

Occasionally, the chemistry is benign. Redmond has strong links with Arsenal, and had been aware of Vontae Daley-Campbell’s reputation as another outstanding graduate of the Afewee Training Centre in Brixton for about a year when he received a text message from the boy’s uncle, Nathan, seeking advice. Their arrangement is informal, but integral.

‘The text was pretty straightforward: “We have a lot of people circling us at the moment. We’ve been told that you’re honest. Would it be OK to have a chat?” We took it from there. People ask – and it is a good question – what the hell do you do for a young player? In Vontae’s case it was simple initial things, like stopping him having to pay for boots and getting him additional nutritional advice.

‘Rather than say, “We will step in from here and do everything,” as others had suggested, I am happy to help prevent him making any mistakes. If the family thinks it is worth us working together more formally closer to the professional phase, and we still feel the same way about them, then that would be great. I’ve been really straight with them.

‘He has the potential to go directly through to the first team at Arsenal, I am certain of that. Will it happen? Let’s see. I never make a promise of that to any player I represent. Look at any team: you can see three players with first-team potential, and many without even a one per cent chance of making it. Vontae is lucky he is in the group that has the potential but it just takes one bad injury, one poor decision, one night out that goes wrong, one coach that doesn’t really fit in with him.

‘Arsenal might sign a Portuguese under-19 international in his position when he is in his second year as a scholar, but I believe in Vontae a lot. I believe he has an excellent chance. An excellent chance for me is still maybe less than twenty per cent, but considering that I think most players have zero per cent, the odds are good.

‘Players always think they have time. They don’t. They have to have a real selfishness, and never really trust that the club have their best interests at heart. They have to have their career’s best interests at heart, and not take any shit. If you are performing well, training well, and you are still not in the team you have to find a way to get out, because that kills a young player.

‘Some of my youth players might be a little more high profile because they score more goals and play in an attacking position. As a defender you tend to be naturally more in the background, but I do think Vontae is the player who will keep quietly doing the right things. He just doesn’t make mistakes. There’s no physical resemblance, but he reminds me of Denis Irwin. Come to think of it, Nathaniel Clyne has those attributes as well …’

There was an unintentional symmetry in the comment. Even the most tenuous connection with the Liverpool full back, Steadman Scott’s greatest ambassador for urban youth, echoes in the tight, cluttered streets around the Brixton Recreation Centre. It begged an altogether more complicated question, of whether another of Scott’s protégés could succeed against the odds.

9

Hope

THE CLOCK ON the wall in a sparse office beneath the main stand at what will be known as the Checkatrade.com Stadium for the duration of a five-year sponsorship deal reads fourteen minutes to three. Dermot Drummy, manager of Crawley Town, has a final team talk to deliver in the dressing room along the corridor, but one last thought to impart before he does so.

‘Tell him what he means to people,’ he says, rising from behind a desk on which sits a dormant laptop, a team sheet and a concise scouting report on Notts County, a streetwise but ageing League Two team that would struggle badly in the winter months, when the club was convulsed by a change in ownership. ‘It will be good for him to hear that. He needs know this is about more than him.’

A little under three hours later, following a 3–1 home defeat in which he conceded a late penalty, I am directing Andre Blackman, Crawley’s left back, to a seat in the visitors’ dugout. He is freshly showered, a little nervous, and oblivious to the hypnotic quality of the small bead of sweat trickling down the outside of his nose.

He smiles slowly, revealing a slight gap between his upper set of front teeth, and chuckles softly when I do his manager’s bidding, and emphasise the wider importance of his struggle to permit his talent to conquer his temperament. He has heard the lecture before, from figures of far greater authority than me, someone with whom he has been in intermittent contact since he was tracked down to a hotel in Fez, a Moroccan city in the shadow of the Atlas Mountains.

A fortnight previously, he had returned to the Brixton Recreation Centre, where his name and his progress were spoken of in hushed tones, as if to avoid the danger of tempting fate. He coached the boys who had come off familiar streets to train under Steadman Scott, the man who was there for him when he was a 7-year-old taking a bus, on his own, across the borough to play football for the joy of it.

‘You can change all these boys,’ Scott told him, when the Afewee Academy session was over. ‘They can relate to you. Three quarters of them will have issues with self-worth. They don’t feel part of this society. But they look at you. People won’t talk about your colour. They will talk about your talent. Dedicate yourself to showing the goodness of this community.

‘Go as far as your ability can take you. Your mother is a good woman. My responsibility is to help you be a man. There is an end product, and that’s why I can be strict with these boys, as I was with you. They will be attracted to you. Making it as a footballer is their ultimate dream. You have that chance. It’s important that you settle down, shut your mouth, and take instruction. Let it happen.’

Drummy, a dapper silver-haired man in an open-necked black shirt, first knew Blackman as a 13-year-old training at Arsenal’s Hale End academy, where he began a career in development coaching that led to his overseeing FA Youth Cup and under-21 Premier League titles at Chelsea. He had spoken to him in similar terms in July 2016 when he decided to give him a one-year contract at Crawley, the latest club in a chaotic career.

‘All I can do is give you hope. I’m not going to pull any punches with you. I am not going to give you false hope. Connect looking after your mum, and the welfare of your family, to your football. This is your opportunity to earn a living, to look after yourself. Money is not our god, but we need to earn it. Don’t ever neglect that side of life.

‘Sit down, anyone who ain’t made a mistake in the world. You’ve been in the wrong. You’ve mucked around and your past ain’t glorious, but let’s step through it and move on. In ten years’ time you could be a role model for someone in Brixton. If I can give you a cause, a connection, that’s the biggest thing I can do for you or any of my players.’

Many managers have tried, and failed, to solve the riddle of a gifted, athletic player and the conflicted, restless young man. His pockmarked CV doesn’t match his post-match persona, since Blackman engages earnestly in a conversation monitored by a young club official silently searching for scraps for the following week’s programme, but it contains too many blips to ignore.

Blackman lasted five years in the

Arsenal academy, flirted with Chelsea and spent a further year at Tottenham before he joined Portsmouth at 16. The arrival of detectives in first-team manager Paul Hart’s office, with a request to interview him in connection with an investigation of a serious crime in Streatham, proved the last straw, despite Blackman’s innocence. ‘A lovely lad,’ recalled Hart, ‘but too much.’

His Bristol City contract, signed in the close season of his release by Portsmouth, was cancelled within three months for what manager Gary Johnson termed ‘disciplinary issues’. An unsuccessful trial at Leicester City was followed by a thirteen-game spell at AFC Wimbledon in what was then the Conference, where his pledge ‘to sort my life out’ remained unfulfilled.

Another unproductive trial, at Oldham Athletic, presaged a difficult spell in which he paid to attend an academy in Tooting run by Jamie Lawrence, a former right winger who accumulated sixteen clubs in a journeyman’s career. When the money ran out, he returned to his roots, and played five-a-side football with friends in Larkhall Park, close to Union Grove in Stockwell.

He was out of the game for nearly a year before repeating the cycle of contrition, determination and rejection at Celtic. Signed on the strength of assertive performances in several development games, he made his Scottish Premier League debut in a 1–1 draw at Aberdeen, when the club were already twenty points clear at the top of the table.

He is best remembered at Parkhead for winning the supporters’ ‘tackle of the year’ award for a sliding challenge in a reserve-team match, where he was unable to prevent himself colliding with manager Neil Lennon, who was pitched, face first, into compacted ground close to the touchline. Lennon’s humour remained intact, but Blackman was to play only three first-team games for him.

The carousel continued. Man of the match on his debut for Inverness Caledonian Thistle, Blackman managed only one more appearance there before his loan was cut short three months early. Terry Butcher, a ferociously competitive player and a notably disciplinarian manager, cited his ‘poor attitude’.

Quietly released by Celtic in November 2012, he was without a club for a further eight months before he signed a short-term contract at Plymouth Argyle in League Two. Discarded after six starts in five months, he spent the rest of the 2013–14 season in the Conference South at Dover Athletic and Maidenhead United.

Owner Massimo Cellino orchestrated an extended trial at Leeds United, which included a pre-season training camp in Italy, but Blackman was overlooked and picked up by Blackpool, who installed him in a hotel with a weekly living allowance of £125. The club and his personal life were in similar disarray. In April 2015 he was convicted of what he described as ‘a moment of madness’, stealing a £1,225 jacket from Harrods; he was sentenced to forty hours’ unpaid community service after the court heard he was apprehended by police, attempting to flee the Knightsbridge store. His future appeared bleak. Raw material – physicality matched by the sort of pace which enabled him to recover quickly from occasional lapses in positional discipline – was being undermined by reputation. At his lowest ebb, when he was a transitory figure, intermittently sighted as what coaches refer to as a ‘body’ in training games, he needed the faith and friendship of men like Chris Ramsey.

Ramsey had wanted to keep the teenaged Blackman when he was Head of Player Development at Tottenham, but, in a scenario that was to become all too familiar, ‘he probably didn’t do himself any favours. The club thought it was going to be difficult to deal with him.’ Having retained contact, he gave him breathing room in the autumn of 2015 by inviting him to train with QPR, where he was promoted from the academy to manage the first team before becoming Technical Director.

‘Do you know how good Andre was? He was fantastic. One the best players I have seen as a kid. His social life and his lack of emotional control stopped him. He couldn’t keep his mouth shut. I got on all right with him, but what he has to remember is that people don’t care about your life. You have to play the game. He is only realising that now.

‘When you are in the game, and there is a way of manipulating your image, there is a chance. When you are outside, looking in, it is more difficult. It will be hard for him to make it in the football world because his reputation goes before him, but I have a soft spot for him. He would be brilliant in the community. He is a good kid, but he has just not been a good kid, if you understand what I’m getting at. He has a lot to offer.

‘The best players, the best sportsmen, use their environment to make themselves better. Those who have the silver spoon, the rich ones who have the best gym and the best nutrition, will use those advantages. Those who come from nothing will use whatever they can get hold of.

‘What we have in the academy system is kids who have never experienced that horrible side of life, kids who think they have a God-given right to be in this clean, kind, supportive environment. Somewhere along the line the fight goes. The ones who are the quickest and the strongest see beyond the veneer.’

Blackman had such vision. He also had the street smarts to text Drummy when rumours of his impending appointment by Crawley reached Morocco. ‘He knew a lot about me, on the pitch and off it,’ Blackman reasoned. ‘I asked if it was OK if I came in and showed what the new Andre is all about.’

The manager smiles at the memory: ‘He started calling me Gaffer. I told him I was going to take my time because I needed to make it right for everybody. I wanted to see how hungry he was. I knew his background. Mine was being brought up on a Stoke Newington council estate. All we had was a ball and hope.

‘I guess I’ve never forgotten that I didn’t have anyone to mentor me when I didn’t make it at Arsenal. I left at nineteen and six weeks later was climbing up telegraph poles as a British Telecom engineer. I went semi-pro and then became a London cab driver. Doing the Knowledge makes you very humble. As a coach, I develop people. I don’t develop footballers.

‘You have to be skilled at, and knowledgeable about, what you do, and point lads in the right direction. Things change. In our generation you stood still when a policeman came down the road. You went into the army. Boys learn in such a vastly different way now. They are thrown into adulthood by the world in which they live.

‘They have to have someone they believe when they are talking to them. I think you can pick people up if there is a trust – and there is a trust between Andre and myself. His mother was ecstatic when we signed him because she knew we would give him a reason to get out of bed. He knows now that talent is never enough.’

Crawley is a homely club, unpretentious and welcoming. Kelly Derham, the chief executive, cleans the toilets when the need arises. Drummy espouses the benefits of sports science on a limited budget, expects his players to fetch and carry on their solitary training pitch, and believes in the power of human contact.

‘I see myself taking time out for my players, not just Andre, but when his gran passed away the other day we made sure Crawley sent flowers. I wanted Andre’s mum to know her son was in a family. Andre is going to be looked after. Andre has guidelines. There is no easy stroke for him. He gets treated the same as everyone else, but he has a shirt to pull on, a cause to go for.

‘There’s many a person who wants to grab a young kid in the spotlight and make some money out of them. The best coach is a community worker, whose best interests are in the kids. Then you make sure they are linked into the right environment with the right guidance. If there are no role models in their life, and crime in the background, there will be opportunities to take the easy way out when things go wrong.’

Blackman’s response may contain customary promises, but they are delivered in a manner that suggests lessons have been finally learned. Arsène Wenger argues the optimal age to gauge a player’s long-term potential is 23, and though Blackman lags two years behind that schedule, his self-awareness gives reason for cautious optimism.

‘I have learned how to control my emotions, and I’ve improved my decision-making in the heat of the moment. Whereas in the past I was more react

ive, I have a strategy to count to ten and just focus. Everyone’s journey is a bit different, you know? Obviously some will say I have gone the long way around it.

‘I wouldn’t say I’m one hundred per cent, but I am nearly there. Some people understand things a bit quicker than others. I have been around younger boys who are really mature. A group of people is about the right mix, different minds and different decisions. Some don’t have the mental strength to push through and fulfil their potential.

‘I come here where people are professional and understand what you have to do. Then I go back to Brixton, and I don’t know what Brixton is going to offer. Sometimes, someone’s been hurt. There’s a lot of boys right now just in and around it, and that’s all they know. I have seen some really, really good players. They are more comfortable just following the cycle.

‘Obviously I have had my ups and downs but I have always known what I have wanted to do, which is to play football. I went to Morocco out of sheer love of the game, to show everyone I still have that drive and hunger. I have been out of the leagues and been abroad. Some players are released and that is it. I look at that and say, how can that be?’

Drummy knows the score: ‘There is no doubt about Andre’s talent, his physicality, but he blows up. It happened a couple of times in training when he first joined us. He was emotional. I had to tell him, “Oi, come on. What the fuck are you doing?” He has performed brilliantly since. If he keeps performing people will start looking at him again. This could be a stepping stone for him.’

Scott knows the scene: ‘You’ve got to look at the positives. Bearing in mind the environment that he’s exposed to, this boy has done a wonderful job not ending up with a criminal conviction. If it wasn’t for football, Andre would either be in prison, charged with murder, or dead. For me, he deserves chances because of where he comes from.’

No Hunger In Paradise

No Hunger In Paradise The Nowhere Men: The Unknown Story of Football's True Talent Spotters

The Nowhere Men: The Unknown Story of Football's True Talent Spotters