- Home

- Michael Calvin

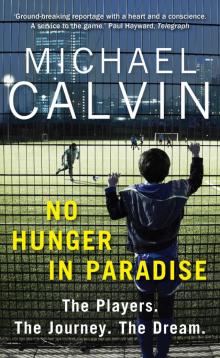

No Hunger In Paradise Page 17

No Hunger In Paradise Read online

Page 17

Drills increase gradually in difficulty and are designed to ‘multitask’ the brain. Boys often play bare-footed to develop sensitivity of touch, and are asked to complete simple mathematical tasks while exercising. Should they neglect their academic studies they are banned from training for up to a month. Counter-intuitively, they are told not to dwell on the mechanical reasons for their mistakes.

Thomas Tuchel, the Borussia Dortmund coach whose stock is high in several Premier League boardrooms, is a disciple. He deliberately compresses space in twenty-a-side training sessions, limits wide players to a small area of the pitch to test their flexibility and ingenuity, and matches two full teams in one half, to enhance touch, quickness and suppleness.

England, it seems, remains a province of closed minds and short attention spans. Samuelsen was regarded as too much of a maverick by Manchester City and though he has broken into senior international football at the age of 19, he has not been trusted in the Football League, apart from a mutually beneficial loan spell at Peterborough, to whom he returned in January 2017. Promises that he would play regularly at Blackburn, a chaotic club with an unpopular manager, Owen Coyle, were not kept.

Frode believes academy football militates against ambition, flair and self-reliance. He uses his son’s experiences to argue that the system abhors honestly made mistakes which, addressed intelligently, would lead to long-term improvement. Coaches prefer the short, safe pass to the surging, jinking run that shows the defender the ball and carries the risk of loss of possession. Their command-and-control culture militates against any young player who prefers to develop his skills by working on his own.

‘Many clubs forget this is meant to be about development, so the story repeats itself. Martin needs to be with a manager who looks at football in a modern way. If you look at his clips and study his match analysis he runs more than most and makes fewer errors, yet he has a reputation for being risky because he doesn’t do the conventional thing as a wide player, and throw the ball into the box. Bias builds up against you.’

This cultural predisposition to narrow horizons extends to the classroom. Teachers at St Bede’s College in Manchester found Martin had an aptitude for learning not shared by British players at the school as part of City’s development programme. In the words of Director of Studies Dr Andrew Dando, he was ‘respectful, polite, but absolutely driven educationally’.

He was ‘gutted’ to attain B grades in Maths, Physics and Chemistry A levels, despite having to do homework and revision on the bus, going to matches for club and country, and relying on distance learning during a loan spell at Barnsley. Less than four months before the end of the academic year in the upper sixth he announced that he wished to study for a GCSE in Biology as part of a contingency plan to enter the medical profession if football didn’t work out.

He was effectively self-taught, since he could not be accommodated in the timetable at such short notice. Dr Dando gave him a textbook and arranged an email account to allow him to ask questions of a specialist teacher, Christine Hennity. He sat the first paper in Manchester, but was in Norway, assisting Wayne Rooney in a coaching clinic, when the second half of the examination was conducted.

There was no room for administrative manoeuvre, and Dando was amazed when Samuelsen still earned a C grade. This meant he had scored above 90 per cent in the half of the examination he was able to take: ‘That must have something to do with what was instilled in him when he was younger, through the culture in which he grew up.’

Too many academy footballers are over-indulged to the point of social impotence. They complete wellness questionnaires each morning and are shielded from realistic criticism by the superficial positivity of support staff. When the going gets tough, they lack the toughness to get going.

Samuelsen wasted no time when City informed him he would not be retained at the end of his under-18 season. He personally organised a ten-day trial at West Ham, a fortnight’s stay at Schalke 04 and a week of scrutiny by the coaching staff at Inter Milan. All were completed despite the duress of his being in the final stages of revision for his A level examinations.

Professional football may ultimately be unable to process his individualism, but he will remain true to himself. The importance of such comfort in his own skin cannot be underestimated, since everyone has his own path to follow, in sport and in life. Some may end up in a cell, but the survivors reach for the stars.

11

Ground Zero

THE YEARS FALL away on a cold, clear afternoon, when a northerly wind carries the portent of winter. Tony McCool has returned to reminisce, and begins at the house in which he grew up, on the Lewsey Farm estate in Luton. He retraces countless childhood steps, along Hereford Road and past the Hindu Community Centre where the elders used to allow him to chalk a goal on the wall, and play football in the car park.

He ventures across Pastures Way to reach the grassland that was once an imaginary Wembley. It is now overgrown, because the council claim they lack the resources to tend it in an age of austerity. Another former playing field, not too far away, is rutted and unusable, the consequence of a bureaucrat’s bright idea – rotivating it in an attempt to create an urban meadow.

The justification for such social vandalism is the architecturally impressive, academically optimistic local college, and the new 3G pitches, funded by the Football Foundation and the National Lottery. The facility is well used during weekday evenings, by portly pub players and club teams of varying standards, yet on this particular Saturday, as on many such Saturdays, the gates are padlocked.

It costs £56 an hour to rent, which, on an estate blighted by social exclusion, vandalism and gang-fuelled violence, is the sort of legitimate disposable income no one possesses. A publicly funded facility is paralysed by market forces. The high, green metal meshed fencing is a forbidding symbol of missed opportunity.

This is England, our England. Our children are among the least physically fit in the world. When the government finances a £200 million anti-obesity drive through sport the money is squandered on an inane marketing campaign and the administrative chaos that accompanies it, rather than invested in coaches on the ground.

When the Football Association partner with Tesco, for a programme of free coaching sessions aimed at children aged between 5 and 11, the project is hamstrung by the necessity to stage lessons between 4 p.m. and 6 p.m., when working parents are unable to provide transport. The reason for the time restraint is simple and damning: private leisure facility owners make the majority of their money on the post-work, conscience-cleansing rush between 6 p.m. and 10 p.m. Their profits are sacrosanct.

McCool has worked in all aspects of football over two decades. He was one of the pioneers in performance analysis software, coached at Luton Town’s consistently productive academy before moving to Queens Park Rangers, and scouted first-team opposition for MK Dons. Now, in addition to youth development work for Norwich City, he supervises in-school activity programmes.

He is understandably wistful: ‘Like most people, I tried and failed to make it as a pro. When you have a tough childhood, it is your dream. Every day, I’m out with a football. I want to get spotted, so I’m in the park playing football. If I tried to play there now, I’d lose a size-three ball in the undergrowth.

‘Now it is pay to play. My mum and dad struggled to feed us, let alone pay for football. Elite athletes can come from any background, from the stockbroker belt to a high-rise council flat, but kids around here are dealing with all sorts of challenges and issues. There are single parents, no parents, poverty of the highest order. There are kids suffering from abuse, disability, learning difficulty.

‘Coaching at a professional club is really quite easy because everyone is motivated. The parents want their child to do well, so they are going to be well behaved, on the whole. You don’t have the grassroots thing on the Sunday morning where the parents are going wild. There are boundaries in place and they probably know that it’s too risky.

‘They’re probably bunking off work. It could be costing them £100 a week to take their kids to an academy, because they could be travelling all over the country. Boys are training four nights a week. They’re drained. Then, in a blink of an eye, someone at the club isn’t having them. They’re dropped like a sack of spuds.

‘The dynamics have changed. When I grew up I played for a really good grassroots club. My parents weren’t there watching me every week. Football wasn’t on TV every five minutes. Now we’ve got everyone there: mum, dad, brother, sister, grandma, grandad. By the way, some of the grandparents can be really lively …’

One of football’s parlour games is to swap horror stories about the orcs who lurk in youth football. Tales abound of tearful teenaged referees fleeing in fear, of parents triggering mass brawls at under-8 tournaments by invading the pitch, and of boys ending up in the local A & E department because they were trampled underfoot, or even assaulted by an adult.

The issue was crystallised by Barrie Funnell, volunteer chairman of the Surrey Youth League, after a weekend in which three games had to be abandoned due to fighting, a parent threatened to stab a referee, a linesman was headbutted and players, egged on by their manager, were only just prevented from smashing up their changing room.

‘The level of outright violence, abuse and disrespect has to stop,’ he wrote in a letter he asked to be distributed as widely as possible. ‘Clubs and everyone involved in trying voluntarily to run children’s football need to take back control from thugs and idiots. Personally, I am sick of seeing this happen, week in and week out.

‘I have heard all the excuses over the years, seen the blame culture. Take responsibility yourselves, get the police involved where you have to, deal with it there and then. Everyone says it is only the mindless few, and that may be true, but why do I, or anyone else, have to look at this utter contempt for the law, and disrespect for humanity?

‘Would you want your name associated with a children’s competition that resulted in the death of someone as a consequence of violence? Don’t believe it cannot happen. It did to a linesman at a children’s match in Holland three or four years ago. If this continues I fear that this may be the result here.’

Even in the cocoon of academy football, Tony McCool has been physically threatened. He was grateful for the corroborative presence of Gerry Francis, the former England captain who has been a long-term assistant to Tony Pulis, when he asked a 14-year-old midfield player at QPR to operate as a centre back as a one-off experiment. The boy refused, went into a tantrum, and was told he would not play at all.

McCool was merely following coaching orthodoxy. He recalled similarly testing the versatility and strength of character of Jay DaSilva, the England under-19 left back, whom he regularly asked to play in a variety of right-sided roles when he was at Luton, before being sold to Chelsea for an initial £40,000 along with his brothers, Rio and Cole. But in this instance, reason was immediately overwhelmed by ignorance and hostility:

‘The dad stormed round the pitch and basically wanted to have a fight with me. Rather than have his son do nothing I’d handed him my notebook, and told him to juggle the team, to see how it could fit together. Was I happy with him? Of course not. I just wanted him to do something constructive. The parent lost his mind, threatening me.’

A protective contingency plan, informed by experience in grassroots football, swung into action. McCool reasoned that if he kept his feet facing the pitch, with his arms behind his back, and refused to face the parent it would signal he was not the aggressor. An official complaint, made by the father, that McCool had thrown a water bottle at the boy was dismissed by numerous eyewitnesses, including Francis.

Problems are exacerbated by the promise of financial reward. When the father of another 13-year-old was agitating to be allowed to leave QPR, with the implicit but illegal support of an agent, the intelligence network of academy parents quickly discovered that the young player had been approached by another club. The request was denied, and the family were reminded that the boy had the right to run his contract down.

‘There was constant to-ing and fro-ing and bickering, so at the end of the season we agreed to say, you know what, we’ll just let him go. When we told the dad, thinking, fair play, that’s what he wanted anyway, the guy went absolutely bananas. He started shouting and bawling and grabbed Steve Gallen, the academy manager, on the stairs at the training ground. We genuinely thought he was going to throw him over the balcony. I don’t know where his boy is now, who he plays for, if he plays at all. It is the lad I feel sorry for.

‘There’s not enough control. Players are getting tapped up at six years old. Big clubs are establishing recruitment centres in productive areas like Luton, approaching players and selling them the dream. I go into schools these days, and I’m invariably approached by a lad who says he plays for the local professional club.

‘My response is, “That’s nice. How many days a week do you train?” “Er, one.” I’m not going to put that child down in front of all his friends, but he’s not a signed academy player. He is in the development centre. The parents are the same. They want something to boast about. Even if their boy is in an academy, the work hasn’t really started.

‘As a scholar, have you made it? As a first-year pro, have you made it? You’ve played ten games in the first team, but have you made it? The best players, the best athletes, the Roy Keanes of this world, will tell you they always want to improve and they never quite achieve. They win a trophy and they think, where’s the next one?’

The dilemma is palpable. McCool confided he had just been asked by a friend to advise the family of a 7-year-old, ‘who, I’ve got to say, is the most talented kid I have ever seen’. He had already ‘been pulled from pillar to post’ by overtures from a variety of clubs. McCool avoided outright recommendations, preferring to analyse the situation dispassionately:

‘Let’s try and look at it from a pragmatic point of view. You live in Luton. Luton’s got a professional football club. The boy is immensely talented. Let’s say he progresses further, until he is fourteen. He is going to go to a Chelsea, a Man United, or a Liverpool. Under the current EPPP structure Luton wouldn’t be able to stop that anyway. If he’s good enough, he’ll go.

‘So why would you want to drive him round the M25 four times a week? The poor kid’s knackered, his schoolwork suffers, he’s in the car, stuck in traffic until midnight. I don’t work for Luton any more, remember. If you lived in Blackpool, he should sign for Blackpool. To be brutally honest, I don’t actually believe he should play for anyone.

‘Clubs should not be allowed to contract a boy until he is twelve. He should play grassroots football, play for his school, play in the street. I think that should be part of the development of any player. It’s less structured, there’s more freedom. I know you get better when you play against better players, but also, just playing with your friends can mean so much. There’s a massive moral aspect to this.’

McCool is an admirer of Nick Levett, the FA’s Talent Identification Manager, who shares his deeper concerns about the standard of scouting at youth level. Levett has delivered bespoke courses to clubs across the four top divisions, concentrating on the enhancement of such soft skills as relationship-building, communication, and the recognition of unconscious bias.

‘A scout at a club I visited said he had just recommended a kid because he reminded him of Alan Smith, the former Leeds United and Manchester United player. So what? Who cares? This lad was ten years old. Why make that comparison? The mindsets will be different. They belong to different generations, different times. They have different DNA, different schooling. They come from different parts of the country. The scout applied his unconscious bias.

‘That drives our own decision-making. As a player, if you’re a hard-working centre midfielder, you would value the traits of a hard-working centre midfielder. You’d think those traits were more important than the creativity of a tippy-tappy winger that doesn�

�t track back. You have a conflict, a misalignment in your values. It’s natural. It drives our prejudices, and drives our decision-making. If people recognise that this bias exists, they will be more effective.’

But football does not operate with neat, philosophical purity. It is a venal world, in which scouts are routinely undervalued. In some, this breeds a mercenary approach. Cash contaminates, undermines, seduces. McCool’s tone hardens:

‘I’m a scout and I’m telling you that you’re a good player. Why? Because I care about your future, or because if you sign for my academy I will get X amount as a bonus? We all can’t do things for free. You can’t ring up your mortgage company and say, “Um, I can’t pay this month, but just so you know, I have helped develop a boy that could be a player in the future.”

‘Things don’t work like that. Everyone has to make a living. I’m cool with that. But if you put financial reward on the table, in any industry, some people will turn into vultures. They’ll trample over anyone, do anything. I’ve seen it first hand in academies, including with the little kids. Players get signed, and released, for the wrong reasons.

‘There was one boy signed after a single training session. I know we all think we are superstar talent-spotters, but I never comment until a boy is two weeks into his trial. He’s a bag of nerves. He needs to settle in, deal with the pressure of knowing no one. Let him make a load of mistakes and then, after he has trained six to ten times, I’ll let you know.

‘It was nothing against this lad, but I couldn’t sleep at night knowing he’d been signed. I was close to walking away. My issue is this: that kid and those parents have gone home jumping and punching the air, like, yeah, we’ve done it. They’re cuddling that kid, brilliant, fantastic. But is it real though? Is that player still in the system now? And if he isn’t, what detriment did it have on his education? Morally, that’s a crime.’

No Hunger In Paradise

No Hunger In Paradise The Nowhere Men: The Unknown Story of Football's True Talent Spotters

The Nowhere Men: The Unknown Story of Football's True Talent Spotters