- Home

- Michael Calvin

No Hunger In Paradise Page 2

No Hunger In Paradise Read online

Page 2

Do not judge harshly those who speak in these pages on condition of anonymity. There are careers to sustain, nearest and dearest to protect. Such voices deserve to be heard, if only to balance the sophistry and self-promotion of an industry that commoditises childhood without deigning to acknowledge the cost.

The world has seen grown men weep. It rarely hears the primal scream of a boy, told he is a failure. This is what it sounds like, when doves cry.

1

Poverty Driven Children

‘WHAT’S YOUR DREAM, son?’

Steadman Scott is sitting astride a silver-grey FitBALL in a glass-walled alcove beside the entrance to the gymnasium at Brixton Recreation Centre. He is wearing a navy T-shirt that speaks of ‘making the impossible possible’. His voice is tender and his brown eyes are wide, yet an unblinking stare hints at underlying hardness.

The boy is 6 years old. He bites his lower lip and lowers his head. He is wearing a pristine white Real Madrid kit, socks pulled fashionably over his knees. His delicate features, long loosely curled black hair and olive skin testify to his mixed heritage. He has an Australian mother; his father, a member of an Arabic Berber tribe from Chad, leans forward and mimes encouragement.

‘Be a footballer …’

The words are mumbled, compressed, barely audible. Scott smiles, shifts a black beanie hat so that it sits behind his ears, and extends his right hand so that it rests on the boy’s shoulder. His gaze is unwavering. The boy does not flinch, but there is a tremor of alarm in his eyes until he sees his beaming father.

He finds the confidence to face his new teacher: ‘If you haven’t got that dream, son, you’re going to have to walk right out that door, and never come back. If you want to stay here you have to prove yourself. You must be strong. It will be tough. I will be harsh on you. But I smell a footballer. Come with me.’

They walk around the fifth-floor landing to a sports hall. Heavy double-doors open to reveal around fifty boys, doing possession drills in three groups. Scott is drawn towards the beginners, and a boy whose tongue protrudes from the corner of his mouth as he concentrates on controlling a ball at walking speed.

The coach kneels, takes his pupil’s right foot in both hands, and murmurs, ‘Knee over the ball, light touch.’ He rises, takes a pace backwards: ‘Yes, yes. That’s it. Put that in your mind. Don’t rush it. Don’t get lazy, now.’ Suddenly, he swivels on his heels, and barks, ‘I’m watching you, too,’ at a more advanced group, who are weaving through blue cones without due care and attention.

Order is instantly imposed. He is looking for indications of mental strength, physical dexterity and technical skill. Bullying is punishable by exclusion, but aggression has its place within clearly defined limits. Scott knows that those who are unable or unwilling to defend themselves drown in the piranha pool of the professional game.

This is a prep school, run on old-school lines. Discipline is enforced rigorously. Training is designed to instil a love of the ball; its intention is to stimulate the imagination, thrill the senses. Conventional tactical education, the straightjacket of team shapes and systems, is left to the professional clubs, who salivate at the raw material assembled in unheralded surroundings.

‘Bear in mind where these boys come from. First of all, I want them to know this is their time to shine, to be the star. If you want me to go mad, pass the ball, risk the ball, and I’ll go crazy. Cherish the ball. Take three touches, two touches. Now I know you’ve got the ability. I’ll teach you one v. one, going past people and defending. My job is to coach you how to play football, not give you a position.

‘These kids don’t get the chance to learn on grass. They act differently here to when they are out on the streets. Their parents don’t exist. They feel safe, because only their dream exists. They know they must follow the rules, my rules. I will shout. I will test their spirit. I am their godfather. This is about preparing their bodies, and their minds, for what is to come.’

He spots more boisterousness out of the corner of his eye and raises his voice: ‘You are a blackboard with nothing written on it,’ he announces, oblivious to the confusion generated by the analogy. ‘This is work. If you are here for fun you are in the wrong place. This is for a reason. We will teach you to hold yourself properly and conduct yourself right when you go to your professional clubs.’

Other supplicants are waiting. A mother pushes two sons towards him. They stand out in a sea of replica kit, since they are dressed in hand-me-down pullovers, grey shorts and black plimsolls. The younger boy is rejected gently, because he is no more than 4, but his brother is told to report the following week. The nominal session fee, £2, will be waived, as it is for so many others from visibly straitened backgrounds.

This is Afewee, the volunteer-driven community club created out of social chaos by Scott and his friend Tony Goldring in 1997. It has produced twenty professional footballers, and more than forty of their boys are among the 12,500 currently in the academy system. One player is spoken of in awe. Clyne. The surname is sufficient.

Scott spotted him, aged 8. He was small, quick and fierce, yet unusually quiet and self-contained. He played cage football until darkness descended and the walkways of Brixton’s interconnected estates were reclaimed by heroin addicts, dealers, and opportunistic knife-wielding muggers as young as 11.

The story of Nathaniel Clyne – told by the tattoo on his left arm, where the inscription ‘Baller from birth’ accompanies an image of him as a toddler clutching a football – is modern fantasy made flesh. As a multi-millionaire, and a senior England international, the Liverpool defender is the ultimate survivor. He embodies aspiration and inspiration.

He was brought up just off Somerleyton Road, in a block of flats colloquially known as ‘Gun City’ or ‘Murderzone’ because of its adolescent enforcers. It was controlled by the Poverty Driven Children, a notorious gang challenged by mutational alliances such as Guns and Shanks, Tell No One, Siraq, Untouchables and All ’Bout Money.

They operated with impunity out of offices initially designated for caretakers, and forced vulnerable families out of their homes, which became a network of crack dens. Addicts would also shoot up behind trees, close to a foul-smelling underground car park into which only the foolhardy or the desperate ventured. Squatters moved in before the block was officially open: a front-page article in the Guardian used it to illustrate John Major’s denunciation of ‘grey, sullen wastelands, robbing people of self-respect’.

Scott saw the good amidst the bad: ‘I saw a young man, very sharp, very disciplined, very good on the ball. Clyne had a bigger brother, Theo. Now Theo was very, very good. More skilful, but he was thinking he was all fancy. He had an attitude problem. Clyne, he didn’t argue. He just got on with it. I asked him where his mother was.

‘When she came I spoke to her about taking him here, upstairs in the Rec. I’d take him in, train him, work on his mentality, and eventually send him to Arsenal. He came from a gang place, but she was a good lady. Very strict. She cared. She understood. She saw our youth killing themselves with drugs, knives and guns. We spoke about hope, the dream. The rest is history.’

Her son scored six goals on trial as a winger at the age of 10, but Arsenal rejected him because he was supposedly too small. Spurs were similarly blinkered, yet Scott reassured Nathaniel there were ninety other clubs searching for someone like him. Clyne excelled at Crystal Palace, made his Premier League debut for Southampton, and was sold to Liverpool for £12.5 million in July 2015.

The system seizes on him as a status symbol, a source of self-justification, but he remains a statistical anomaly. Less than one half of one per cent of boys who enter the academy structure at the age of 9 will make a first-team appearance. More than three quarters are jettisoned between the ages of 13 and 16.

The odds get no less intimidating the further a boy progresses. Almost 98 per cent of boys given a scholarship at 16 are no longer in the top five tiers of the domestic game at the age of 18. A recent study

revealed only 8 out of 400 players given a professional Premier League contract at 18 remained at the highest level by the time of their twenty-second birthday. Since only 180 of the 1.5 million boys who play organised youth football in England at any one time become Premier League pros, the success rate is 0.012 per cent.

Margins are fine and critical decisions are occasionally taken arbitrarily. They are influenced by political nuance, naked self-interest and nervousness stimulated by suspicion. If natural talent was the determining factor, Andre Blackman, an Afewee contemporary of Clyne who was eagerly signed by Arsenal as a teenager, would be playing in the Premier League.

Instead in May 2016, at the age of 25, he was attempting to reinvent himself at MAS Fez in the Moroccan Botola league. His athleticism and sense of adventure from left back made him a favourite of the Fatal Tigers, one of North Africa’s biggest supporters’ groups, but exile at the thirteenth club of a bewilderingly indisciplined career was not without its challenges.

‘I come in at half-time and suddenly I’m alone,’ he explained, with a telling sense of bewilderment. ‘The rest of the team goes into another room to pray. They’re like magicians on the ball, but without a brain. They go for goal, work an opening, and can’t stop themselves doubling back to try to beat their man again.

‘The football is technical and they want me to stay for another eighteen months, but I’m not sure. The manager got sacked at the end of March and we’re in danger of going down. To be honest, I’ll have a look around when I get back to England in June. Not heard anything, have you? My agent will sort the rest.’

Blackman’s struggle, and Clyne’s success, has special resonance in an area defined by deprivation and social contraction. There are more shootings in the borough of Lambeth than in any other part of London. Life expectancy amongst males is five years lower than the capital’s average. The crime rate on the estates is double the mean, the robbery rate triple. Almost two thirds of children come from single-parent families.

Yet Brixton remains a vibrant community, despite the social schizophrenia of gentrification over the past five years, which has inflated rents and led to simmering tension. Football has wider significance, collective importance expressed through the interdependence of four of the principal figures in Afewee, which, loosely translated from Jamaican patois, means ‘It is for we’.

Scott, the figurehead, is 60, but when engaged, channelling private passions and enduring frustrations, he appears at least a decade younger. He is a commanding character, who manages to minimise and disguise the handicap of having only 40 per cent mobility – the legacy of a chronic back injury sustained during unsupervised weightlifting sessions when he was in prison.

‘Young boys trying to impress each other, squatting, lifting big weights with no instruction, no technique,’ he explained quietly. ‘When I leave Her Majesty’s confinement I was coaching and had a bag of footballs slung over my shoulder. Suddenly, something clicked. I collapsed and couldn’t move for six months. I thought my life was over.’

When he is not at the Rec, he can usually be found lying on the floor of his flat, less than half a mile away, to ease constant pain. When he is there, nodding sagely and bowing respectfully to those who seek his confidence or advice, he is in his element. He mistrusts those developers who have designs on the centre, opened in 1994 as a consequence of Lord Scarman’s condemnation of a lack of local leisure facilities.

‘This is my temple. This is my church. This building gave me life. This building create I. This building is history. As a Brixtonian for fifty years, I don’t call this the Recreation Centre. I call it the Re-Creation Centre, because it was meant to re-create my generation, and future generations. It is for the community. It is for us.

‘Our mission is to put belief, passion, hard work and discipline into our youngsters. When I was first around here there was nobody to motivate us. Imagine yourself as a ten-year-old with a speech impediment, newly arrived from rural Jamaica. In the sixties, black people didn’t have an identity, didn’t have a voice. You were invisible because of the colour of your skin.

‘My memory of an English education is of sitting at the back of classes. I was scared people would laugh at me. There was one teacher, who sit down with me and take time, so I can break down the word and pronounce it. This lady showed me passion, patience, discipline. She made an impact so big that the principle of Afewee was based on her classroom. We try to inspire.

‘Our youngsters are in gangs. Why have they gone astray? Why did my generation go astray? As a young man in the seventies I couldn’t find no job to give me self-esteem. There was no black people working in no Barclay Bank, no black people in no government office. Guys like us, who came for a better life, had only sus laws, stop and search.

‘Just imagine, late at night, if you are out of your community. You have to hide from police, racist white guys. This environment led to riots in 1981, 1985, 1995. We chose not to follow our fathers, the Windrush Generation. We weren’t content to be content. We decide to have dreams. We embark on the street. The system criminalised my generation, turned us into rebels.’

Societal revenge was swift. To use Scott’s plaintive phrase, ‘the judge slaps me in the face’. He was sentenced to six years for a drugs offence he continues to dispute. It proved to be a pivotal experience; he studied counselling theory and summoned the inner strength to survive personal trauma.

‘My life outside fell apart. After eighteen months my wife wanted a divorce. I said yes, I can’t afford to argue. If you want to do it, do it. You can’t cry or do crazy things when you are inside because it will only get you a longer sentence. You have to take a deep breath and cope with it.

‘I am sitting in my cell and I look deep into myself. What was my strength when I was walking the streets? I was a qualified football coach, weight trainer, swimming teacher. What was my passion? Helping young boys. I tell myself: “Stop chasing money. The grave is coming near. What is the purpose of your life?”

‘When we’ve passed away people will talk about what we have done. This is about how you treat your fellow human being and your community. I can talk about how I love my community because I do this for free. If you show a kid love and respect, attempt to understand his world instead of leaving him to his own devices, he will not rob or kill your kids.’

Peter Armstrong, secretary of Afewee Training Centre, also assists their boxing programme, established under head coach Bobby Miltiadous in response to the 2011 riots. An openly gay former university teacher, who set up an HIV charity following his diagnosis with the condition in 1991, he provides administrative rigour and philosophical support.

‘For Steadman, Afewee works at that level of helping to ensure equality within the community, and particularly Brixton. It was his experience that such equality was so lacking it led to chaos, which led to legislation. This is not just a football organisation, because its success leads indirectly to social progress.

‘Kids can learn ball skills quite quickly. But will they have the attitude to practise and practise? Will they be able to deal with Steadman’s shouting, the badgering, the repetitive drills and the commitment to come here three times a week? It is those sorts of qualities which will make them successful in life.

‘People talk about teaching kids confidence, self-esteem, belief in their dream. I don’t think that can be taught. It is instilled into the kid by exposing him or her to an environment which allows the development of those competences. A good coach does that, and that is all the justification you need for promoting sport.

‘You don’t have to march the kids into the classroom to teach them life skills. Nobody can teach wisdom, patience, tranquillity or serenity, because those higher-level competences are innate, but our kids are gaining experience of self-mastery on and off the pitch.’

Tony Goldring, the principal football coach, first met Scott at a course for the unemployed in 1990. They are similar in terms of background, since he admits, ‘I turned into a bit

of a bad lad,’ due to a lack of positive role models. His under-8 team, London champions in the 2015–16 season, were unbeaten in twenty-nine matches, but he recognises results are of marginal significance, compared to the pastoral nature of his work:

‘Football has the capacity to teach children to be confident, proud, never to settle for second best. They are encouraged to excel, inspire. We have had our struggles, but if a programme like ours didn’t exist there would be more crime. Dysfunctional families would drift. Let’s not kid ourselves. There are massive problems. There is still a huge divide between haves and have-nots.

‘We attempt to embrace everyone. It is a bigger responsibility, but part of our job is to develop the emotions and qualities which help to produce a better citizen, who is better equipped for life. Never forget these boys and girls are the fathers and mothers of the future. By embedding discipline and promoting self-worth, we are helping the community to help itself.’

Jay Jay Lodge is Afewee’s emissary to a darker world. He uses his ‘Spare Everyone’ initiative, designed to offer freedom of movement across gang boundaries, to secure safe passage for the boys. A large, loose-limbed man with an easy laugh, he has the zeal of the convert and a backstory that justifies his observation that ‘I hold a lot of weight around here’.

He was sufficiently promising, as a defensive or left-sided midfield player, to be signed by Crystal Palace at 14, and trained with the Jamaican national team when he briefly returned to his native island. His moment of clarity came in Brixton prison, where he was serving time for hospitalising three men who attacked him. He could see his flat through the small, barred window of his cell, and resolved to change.

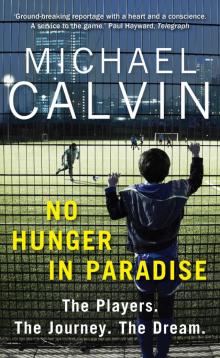

No Hunger In Paradise

No Hunger In Paradise The Nowhere Men: The Unknown Story of Football's True Talent Spotters

The Nowhere Men: The Unknown Story of Football's True Talent Spotters