- Home

- Michael Calvin

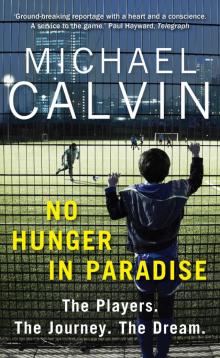

No Hunger In Paradise Page 4

No Hunger In Paradise Read online

Page 4

‘Professional clubs aren’t bothered about that. Then, however many years later, they discard one, two, or all three of the kids they have taken, often in a way that shows very little duty of care. Some English clubs, like QPR, are great in investing proactively in the grassroots, but, generally, it is certainly not a two-way relationship. Most just cherry-pick and hope something turns up.’

Dutch clubs, by contrast, have a holistic approach. AZ Alkmaar, typically, are in partnership with 120 grassroots clubs. They offer coaching seminars, website links, and advice from sports science staff on the principle that the broader the base, the bigger the opportunity. Money is not an issue at the highest level in England; entitlement and expedience are twin curses. The sense of social identity that inspires Athletic Bilbao, for instance, to invest 1.2 million euros in a three-year integration programme with 140 local clubs is an alien notion for the majority of sides in the UK. Even QPR’s relatively enlightened approach only involves the donation of £50,000 to four partnership clubs.

Levett is a chinos man in a tracksuit, an earnest, technocratic type more generally found utilising thinking-time on the beanbags at Google’s UK headquarters than in draughty school halls, preaching football philosophy to the converted. He coached part-time at Fulham for six years, but has a wide background, spanning primary school teaching, sports development initiatives, and experience in women’s and disability football.

‘I look back now and think, nah, I was never a coach. I was a technical instructor or a football organiser. It was from working with educators like Derek Bradley at Fulham and Pete Sturgess at the FA that I began to realise that coaching is about developing people.

‘In my second year at Fulham I had a very challenging group. There were a few big characters, tough kids, inner-city London kids. I spent a lot of time working on them as individuals, conflict resolution stuff, so they would get better at working with others. I’d challenge them, “How are you going to manage it when someone has a different opinion to you about a tactic?” and deliberately put them into situations where I knew there would be issues.

‘My intention was to encourage, support and develop their thinking skills, but I got pulled in by two of the full-time members of staff, for doing too much “social stuff” and not enough “football stuff”, in their opinion. Four years later, it was the worst group in the club for bullying and racial tension, because they spent too much time on football and didn’t deal with the people.

‘I had a kid, in a younger age group, who was the best in his group. A couple of years later, when he had left me, I sat in a coaches’ meeting when they were talking about him. They were letting him get away with things because he was still the best. That was bollocks, the complete opposite of what they should have been doing. There are boundaries and structures that everybody has to conform with, because it’s a team, and the impact of not managing that causes all sorts of issues.’

Signs of psychological stress are easy to miss. Levett was struck by an Instagram post by a 14-year-old whose progress had been halted by injury. It was a cartoon image, of a boy surrounded by material rewards, cash, a car and a phone, and people shouting at him. The implications were inescapable: it was a pictorial representation of unsustainable pressure.

‘The fear, for that kid, is of suddenly not being a potential footballer. The psychological impact of that is huge. So what support is there for those kids? Who picks up those pieces? In many cases the answer is nobody, and that’s where we are failing our kids. We’ve got more resources than we’ve ever had in the game, and I think that, as adults, we should be embarrassed we let such things happen.’

The principles are sound, but are they applied on the ground? Part of the process of discovery involved a tortuous five-hour drive around a gridlocked M25 to Hinchingbrooke, an idiosyncratic state school set in the grounds of what was once Oliver Cromwell’s family home in Huntingdon. His audience, over three hours in the Performing Arts Centre, consisted of seventy local coaches and youth recruitment officers.

Familiarity lent them a certain comfort, and they conformed to type. Some wore training tops emblazoned with their initials, the symbol of the clipboard warrior. Others failed to engage consistently, evidently seeing the evening as a box-ticking exercise in their pursuit of an enhanced coaching badge.

Sprinkled amidst the buzz phrases of personal development – extroverts are ‘solar-powered’, introverts are ‘battery-powered’, and poor coaches have ‘a knowledge shield’ which deflects innovation – was an invitation to think differently. How many were willing to embrace Levett’s core message that psychological and social skills are of equal importance to technical and physical attributes in the modern game?

‘Creative kids don’t like to conform,’ he told them. ‘They have a need for originality, but are released from clubs by coaches who have different value systems and beliefs. You can’t make a kid adapt to your view of the world. How do you know who the learners are? Search out the kid who is curious. He will practise on his own without you. If they rely on you they are not going to be distinctive. Your job is to make yourself redundant.’

He spoke of coaching as an intuitive process, in which the clues to a young player’s driving forces and definitive characteristics are subtle, but strangely obvious in retrospect. Creativity cannot be constrained by time; the Dyson vacuum cleaner, for example, is the product of 5,000 prototypes, tested over fifteen years. Information in youth football may border on the banal, but the picture it helps to develop can be sharp and significant.

Which boy carries his bag to training, instead of delegating the duty to his dad? What is the player’s mood, especially if he comes from a broken home? How does he relate to the parent who ferried him to the session? Does the parent stay, and take an interest in his progress? Who has furthest to travel? Is anyone having problems at school? What are the underlying reasons for a lack of concentration and commitment?

Such questions were given focus by the practical session, staged in fine rain on a warm, misty evening. Delegates were asked to critique a twenty-minute seven-a-side match between two local under-9 teams on an undersized 4G pitch. In a re-creation of an old scout’s trick, they were ordered to pick one boy, and concentrate on him entirely for the duration of the game before reporting back.

Like many observers, I chose Josh, the youngest and smallest boy, who played conveniently close to the touchline along which most of us stood. He was skilful, given time and space, but when he evaded a covering defender with a neat, quick turn he was scythed down by two bigger boys. He lingered on the ground for fully thirty seconds, picking pieces of rubber crumb from his mouth before being brusquely substituted.

Delegates described obvious traits and reached predictable conclusions in Levett’s debrief. They reflected principally on Josh’s lack of communication, which signalled a lack of confidence, but failed to notice the aftermath of his replacement. He was ignored by the two young coaches who oversaw his team, and spent the rest of the match sitting on his haunches with his head in his hands.

The lack of emotional intelligence in such treatment, and the wider failure of Levett’s group to recognise the potential damage to the child’s morale, was telling. Had any of the delegates summoned the curiosity to speak to the coaches, or the parents waiting behind the mesh fencing, they might have learned that Josh was a new player, in an unfamiliar environment. His inferior blue team was a composite group, unstructured compared to the cohesive nature of the winning yellow team, who had played together for several seasons.

The lack of deeper insight put into perspective Levett’s attempt to invite his audience inside the mind of that 7-year-old: ‘At that age a boy makes his decision to pass the ball on trust. He is asking himself, “Can I kick it that far? If I do will I be accepted by my teammates?” He has to manipulate the ball, retain his balance, control his limbs. He has to change direction, show speed and flexibility. Are we too quick to say what he can’t do, and write him off?’

<

br /> Football has largely moved on from the absurd Lilliputian spectacle of 10-year-olds playing eleven-a-side matches on full-size pitches. But if the imposition of a senior structure on youth football is being addressed during the early years there are still too many issues, created by unreconstructed attitudes and unrealised ambition, in adolescence.

‘When we get in the youth development phase, twelve to sixteen, one of the major challenges involves the coach’s ego starting to kick in. Kids, who are already going through big changes in life, go from a world of creativity and experimentation to one in which there is pressure to win. All of a sudden you see people on the side of the pitch shouting, screaming and bawling, because they think it helps. I’m not convinced it does. There is no evidence to suggest it is an effective way to help people learn, but as you go higher up, the pressure felt by adults is transferred on to the pitch.’

Levett cites Eddie Jones, the England rugby coach, as a prime exponent of measured leadership. The Australian demanded the highest personal and professional standards in rapidly implementing a culture shift after a disappointing World Cup in 2016. Players were encouraged to take ownership of the gameplan and empowered to make instant decisions for themselves in highly pressurised situations.

The most promising young players need to be hauled out of their comfort blanket, kicking and screaming if necessary. Just as Ajax youth coaches tested Dennis Bergkamp’s resilience by dropping him an age level, and ordering him to play at right back, a League One club took the advice of their sports psychologist and dropped the team’s outstanding player to the bench for a Youth Cup tie to gauge his response to the disappointment. The importance of his development outweighed the importance of the result.

Similarly, Levett structured a series of challenging situations for Nottingham Forest’s under-11 squad. In one drill they had to imagine they were a goal to the good with ten minutes to play against their greatest rivals, Derby County: how would they deal with the stress? In another they were losing 2–0 late in the game in an FA Cup tie against Manchester United: would they retain their spirit and ambition until the end?

The most revealing session involved Levett briefing the referee to be deliberately biased against one team: ‘The biggest kid completely lost the plot. He walked off the pitch and wouldn’t talk to his coach. He couldn’t handle the unfairness but was left alone to think things through. After ten minutes he came back and apologised.’

Levett believes in giving even the youngest players the opportunity to organise their own warm-up sessions, instead of being overseen by academy support staff. The antithesis of such freedom is the goalkeeping coach who walked along the touchline at an under-14 tournament for Category One academies, so that he could line up a wall for his goalkeeper as he defended a free kick, twenty yards out on the right-hand side of the pitch.

‘Now, when they release that goalkeeper for poor decision-making, who gets the blame for that? The goalkeeper coach is responding to his own ego, thinking, well, if I don’t get this right then there’s going to be an issue. Let the kid fail. Let them make mistakes. Then support them and talk to them about it afterwards.’

I had seen something similar in an under-16 game at Tottenham, when an away team coach came on to the pitch following the concession of a goal. He manhandled his central defenders into the positions that would have enabled them to better defend the decisive cross. It had the air of adult arrogance, and created the immediate, undoubtedly unworthy suspicion that the coach was showboating.

Talent doesn’t necessarily announce itself with heavenly choirs or psychedelic colours. Progression can involve random chance or a decision made on nothing more substantial than a gnawing feeling that all has yet to be revealed. Gareth Bale was, for instance, a skinny boy from an external development centre in Bath who earned his Southampton scholarship by a single vote.

Levett’s presentation highlighted one of Lionel Messi’s earliest youth team photographs. He stood at the end of the back row; since at the age of 9 he was four inches below average height, he was dwarfed by those around him. Designed to reinforce the folly of releasing small boys too soon, the image took me back to a chilly evening in Doha in February 2016, and a meeting with Josep Colomer, Messi’s mentor.

As Barcelona’s youth director, he played a pivotal role in the development of a painfully shy and patently driven boy who had been discovered in Rosario, Argentina. Their relationship contextualises the familiar story of the creation of the planet’s best footballer, involving a self-administered human growth hormone programme and a politically charged, financially driven eighteen-month delay before he was confirmed as a Barcelona player at 14.

Others, like Barcelona’s former technical director Carles Rexach and the late Joan Lacueva, administrative director at La Masia academy, were significant advocates, but Colomer’s bond with Messi has a familial feel. Bald and squat, he is the wise uncle who weighs his words carefully, uses his experience astutely and allocates his praise sparingly.

When we spoke, at the twelve-team Al Kass International Cup, the two of them had just returned from Senegal, where Messi supported Colomer’s campaign to distribute a million anti-malaria nets as part of Football Dreams, a talent identification project spanning fifteen nations in Africa, Asia, Central and South America.

Colomer, assistant to Luiz Felipe Scolari with Brazil’s World Cup-winning team in 2002, has the restless eyes and carefully cloaked emotions of his trade. Our conversation, conducted during a fraught under-17 match between Inter Milan and Estudiantes on the $1 billion Aspire campus in the Al Waab district of the Qatari capital, incorporated the wider cultural lessons of Messi’s eminence.

His instinctive mistrust of modern European football, which he describes as ‘a bubble of money and hysteria’, puts him at odds with the orthodoxy of the English academy system, which is indulgent in nature and extravagant in its setting.

Colomer spoke of immediately recognising Messi’s visualisation of opportunity, and the adhesive control that testified to hours of selfless, solitary practice. Yet of greater long-term significance, when he oversaw his initiation in Barcelona’s under-16 team, was evidence of the unusual mixture of hardness and humility he seeks in those whose natural talent might otherwise mask weakness of character.

Like many of his generation, Colomer insists young players need the discipline of old-school chores, such as cleaning the boots of senior players or sweeping the dressing rooms. He uses Messi’s example, of a naturally adaptable player developed on clay or threadbare artificial surfaces, to support his argument that pristine facilities can be counter-productive.

‘Give too much to the boys, and they don’t understand the steps they need to take. I have to tell people, “Look, Leo Messi was training and playing every day on very old, ugly pitches at Barcelona.” Messi is Messi because we obliged him to earn all the steps, in football and in life. He even passed through Barça C, and nobody went there before I changed the philosophy.

‘I have seen plenty of young players with his talent, plenty. Some had a little bit less, some a little bit more. They were at the top, top level, but they did not have his mentality. Leo, he was always a winner, he believed in himself a lot, but he also has a lot of patience for football.

‘I remember when I put him in Barça B. They played on the Saturday. On the Sunday morning he took the bus with the under-16s, his team, to go and support them any place in Catalunya. He was living only for football. So I’m very happy for him because I love him as a person and a player. He is a model for many children who think this is easy. It is not easy.’

The fate of Messi’s contemporary Leandro Depetris, another Argentine phenomenon who became a cause célèbre when he signed for AC Milan at the age of 11, is instructive. His career effectively ended at the age of 28 in the summer of 2016, when he was released by Sportivo Patria, a club in Torneo Federal A, the regionalised third division of the Argentine league.

His is a tale of homesickness, fecklessness

, financial turmoil, over-expectation and underachievement. A striker, he is mocked not only by poignant footage of him as a joyful 8-year-old, weaving through massed ranks of defenders, but also by his professional record, of scoring a single goal at twelve clubs in Italy and his homeland.

‘A cook sees a soup and only by smelling it he knows whether he is missing salt or not,’ Colomer reflected, with faintly inappropriate lyricism. ‘Our job is to discover players and of course we can make mistakes because we are not discovering a player for today, we are discovering a player for tomorrow.

‘That is not only depending on the quality of the player. It’s depending on his progression but also the style of the club, if it fits to his potential. Will a coach of the future like him or not? Will you be at the right place at the right moment?

‘I will put an example to you: if there is a number ten at Barcelona who is a very good young player, is he going to play in the place of Lionel Messi? OK, he has no chance. So the development of a player is not only about his quality. A player grows in a system, but more than a system, a philosophy. Messi has in his body the philosophy of Barcelona.’

One of the enduring issues with the English game is its indistinct philosophy, largely untouched by the FA’s so-called DNA strategy. Levett, who admits, ‘It is narrow-minded to think we have all the answers,’ is at least seeking external examples from sport, business and the arts, to add weight to the case for change.

Strategic links with sports like rugby union, cricket and hockey, aligned to study of elite recruitment programmes at city investment banks, cover common ground in talent discovery and development. Pixar’s corporate philosophy, which speaks of valuing experimental mistakes because ‘without them we’d have no originality’, has also been heeded.

It is doubtful whether football has the philosophical maturity to learn from the Knowledge Is Power Program, a network of free open-enrolment schools in underprivileged communities across the United States, but the attributes they demand in their pupils – social intelligence, grit, zest, gratitude, optimism and curiosity – are directly transferable to professional sport.

No Hunger In Paradise

No Hunger In Paradise The Nowhere Men: The Unknown Story of Football's True Talent Spotters

The Nowhere Men: The Unknown Story of Football's True Talent Spotters