- Home

- Michael Calvin

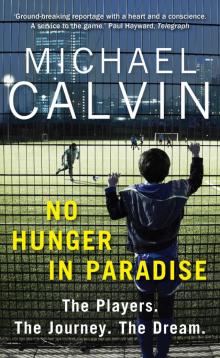

No Hunger In Paradise Page 8

No Hunger In Paradise Read online

Page 8

Brentford provided them with contacts, but the parents’ unconditional love led them into a netherworld of ignorance and rejection, where they blindly chased up unanswered telephone calls or emails in the hope of arranging a trial. Their vulnerability was blithely used against them by those who are accustomed to applying power without the encumbrance of personal responsibility.

Most parents were wary of publicly analysing the process, because they didn’t want to jeopardise their sons’ prospects. But one, who spoke on condition of anonymity because of the sensitivity of his job, was so affronted by its amorality he was prepared to provide a devastating insight into the hidden struggle for a second chance:

‘There is very little common decency. They’re all spivs. They have delusions of grandeur. What do they do between the hours of nine and five? Nothing. It’s only between five and seven in the evening that they actually have a little bit of power and they abuse it. There are too many coaches playing God.

‘One said to me, “You give me something and I’ll get your son into a club.” He was looking for a position for his son in my world. I can’t do that. Sorry, it doesn’t work that way. My son has been in an academy setup for a number of years, but that surprised me. It is a very, very murky and very incestuous world. It is not about how good the boy is.

‘It is unregulated. There is a serious lack of duty of care and an element of, I’ve got my kit on, I’ve got my jacket on, you do what I say. For me, it was always going to be a love affair. It was never going to be a marriage to football, simply because I don’t see football as being the industry that I want my son to go into.

‘If I want him to go into a proper profession, where he can make his own way in life, a football certificate, or being player of the quarter, or a signed player, is not going to carry him anywhere in the world that I’m working in. Qualifications count, so he will make his way like that. Football is an add-on. If he prospers in that we will support him but school has to come first.

‘I’ve seen parents with pound signs in their eyes. That’s all they have, they don’t see beyond that. Everything is geared up to little Jonny being the big professional footballer. They don’t realise what’s going to happen if he fails in his education. He’s either a footballer, or he’s nothing else. Now, I look at things quite differently.

‘It has got to the point recently, because of the closure of Brentford, that I find they are trying to get me to beg. And I’m not going to beg you for a position. Take my son on for what he is, and for what he’s achieved. I don’t see him as a cash cow or a commodity.’

Happily, the majority of the Brentford boys were taken on by other clubs as summer ebbed into autumn. Their reputations preceded them and they dispersed to Norwich, QPR, Tottenham, Crystal Palace, Coventry, Fulham and Wolverhampton Wanderers. The intelligence system in youth football is so sophisticated that one under-15 player was given a chance to earn a scholarship at Southampton, who, like Tottenham, had compiled a player profile on him over the previous eighteen months.

But, just as a stormy sea can swallow a ship without trace, before subsiding into placidity, the restoration of calm was deceptive. A vision, indistinct but increasingly disturbing, was starting to acquire shape and texture. I asked a father what he expected of a football club, and could not get his expression of faith, and the fragility of his trust, out of my mind:

‘The minute he crosses that white line, we entrust him to you. Do what you think is right. Educate him. Help him. Make sure his feet are firmly on the ground. Don’t start throwing money at him, because at his age they take leave of their senses. Don’t allow them to float around in cloud cuckoo land, because they will lack hunger and desire.

‘Most of all, my son has got to be a boy. He’s got to do things that little boys want to do. He’s not manufactured for a football club. He’s our flesh and blood and he belongs to us. We give him to you and we trust you to look after him. Forget about the house, and what we’ve got in the bank account, he’s the most precious thing we’ve got in the world …’

5

Family

CAN A LOGICAL limit be placed on parental love? When does the most powerful human emotion become too much to bear? What happens when the constituent cells of pride and devotion divide and mutate? How can intimate relationships survive external pressure? Are family bonds, tight and sacred, suddenly shredded by the strain?

There are no easy answers, but the questions intrude as the setting sun embroiders the southern bank of the River Don, and the valley in which Sheffield sits. Zak Brunt is being tutored by Miguel Ángel Llera in the far corner of the outdoor Power League complex, which overlooks the Hallam University athletics track.

Watched by his father, Glen, and his mother, Rachel, he warms up by caressing a football on a string hanging from his black body harness. Even at the required rate of sixty touches a minute it is possible to be languid. The ball inscribes an arc as it is manipulated, first by the outside of Zak’s orange boot and then by the instep. Left, right, left, right, left, right. Parade-ground perfect.

Llera, the former MK Dons, Charlton and Sheffield Wednesday defender, throws a second, unfettered ball into the mix. The boy, relatively slight but completely engaged, must pass it back while maintaining the rhythm. ‘Keep watching the sky,’ the coach urges, as he seeks to encourage flexibility, agility and sureness of touch. ‘C’mon. Bap, bap, bap. Give me a half volley.’

They move to a plyometric ladder. Zak must dance through it at a high tempo, continuing to control the balls being tossed at him at different angles and speeds. ‘High level of concentration … can you feel it? Of course you can … good touches … high knee … landing on your toes.’

Llera develops the drill, moving into the centre of the heavily rubberised five-a-side pitch to fire passes at hip height. The boy is expected to follow a deft first touch with an accurate side-footed finish into a portable miniature goal: ‘Pivot. Get your body position right.’

They progress to resistance work. Zak is tethered to the main goalpost, ordered to run forward and leap over parallel lines of cones before the tension in the cord pulls him back to the starting point. He grimaces and sprints again, weaving through five more cones, set at 45 degrees to each other.

The coach’s commentary has a complementary urgency: ‘Quicker, quicker, quicker … bend your knee … bap, bap, bap, bap … don’t let the tension be stronger than you … keep your focus now you are getting more and more tired … this is when the challenge comes … come on, don’t stop the gas … this is the ninety-fourth minute.’

Llera relents, and speaks softly to his pupil in Spanish as he frees him from the yoke, like a horse whisperer let loose in an unsaddling enclosure. Even in the sodium-shaded shadows cast by four-bulb floodlights, the sheen of sweat sparkles on the boy’s forehead. He is breathing shallowly, exhaling before he swigs energy drink from a sports-capped bottle.

‘I love watching him,’ confides Rachel, a small woman who laughs at the memory of the chaos caused by his childhood habit of using the living room of their home in Chesterfield as a playground. ‘We lost count of the number of ornaments he smashed, kicking a ball around. The dog couldn’t get out of the way quick enough.’

Glen, who stands alongside the fence cupping his hands around a container of black coffee, has a natural intensity. As such, he is the perfect narrator for his son’s story. Zak may only be 14, but he has crammed enough incident, opportunity and disappointment into his football experience to accommodate a lifetime.

His training kit, first worn during an open trial for Chelsea in May 2015, offers a hint about the nature of the journey without revealing its harshness and complexity. The numbers, 215 on the light blue top and 214 on dark blue shorts, testify to the scale of the audition.

Zak had just turned 5 when he was asked to join a pre-academy group at Sheffield United. He was invited to breakfast with the first-team squad and posed for photographs with Gary Speed. At 6 he emulated a 12-year-old Davi

d Beckham, and won the world schools’ skills title at Manchester United Soccer School.

Sky Sports News did a live link from his first training session back at Sheffield United. He continued to spend Saturday mornings there, but devoted two midweek nights to Aston Villa, at their Bodymoor Heath training complex, and a third night to Manchester United, at the storied old training ground, The Cliff.

‘All I go on, as a football dad, is, oh, Aston Villa is bigger than Sheffield United. So, of course, we’re going to give that a go. Then Rachel took a call from United, and rang me at my mum’s. They wanted Zak to go up there. We were all United fans at the time, so we couldn’t knock that back. When I consider it now, I think, what was I doing? I’m ashamed, to be honest.

‘We didn’t want to burn bridges, so it was a case of school, sandwiches and homework in the car. Zak was looking at me and his mum as if to say, “What do you think?” We’re new to it, naïve, so he picks up our excitement. He’s a good kid. I’ve spoken to him about it since, and he felt that he needed to go on with it because it was what we wanted him to do. Mum and Dad want to take me here, there and everywhere. I don’t want to let them down.’

The tone is confessional, unstinting, lacerating. Glen Brunt is prepared to admit to what is usually regarded as inadmissible evidence of parental weakness. That takes a distinctive form of moral courage, and unstinting self-awareness, because his demeanour suggests it triggers potentially self-destructive emotions:

‘During Zak’s younger years I had a lot of fury at him. He generally played up an age group and did well. But on this day, at The Cliff, he was not on it. We were coming down the motorway and I completely lost it. I’m screaming and shouting at him. He has a vacancy across his face, which just makes me more angry.

‘I’m going, “Don’t you realise? Best and Charlton played on that pitch. Do you know what I mean?” Of course he had no concept of what I was going on about. He was just six. Rachel had a word with me when we got home. She said, “It’s not him that needs to change. It’s you.”’

He realised his relationship with his son had become dangerously constricted, since it depended on whether Zak had reached perceived standards of excellence. His immediate response, to enrol on a sports psychology course at the Open University in an attempt to gain a deeper insight into the power of the mind, did not alter the priority: choosing the club at which Zak would take an academy place.

‘We had the bright lights, big city syndrome, and were torn between Villa and Manchester United. We had met no bad individuals at that stage. Everybody was hunky-dory. There are good people in the system, but there are also a lot of second-hand-car salesmen. They crawl all over you to buy the vehicle, and get the signature, but when they’ve got it they’re suddenly busy. They’re not interested.’

The Brunts opted to accept a contract from Villa, and moved into rented accommodation in Staffordshire, closer to Bodymoor. It was a fundamental family decision, since Glen and Rachel are officially registered carers for two profoundly disabled sons. Each has cerebral palsy; Niall is wheelchair-bound and reliant on twenty-four-hour care while Rees, his twin, is partially sighted, registered blind. A fourth son, Liam, almost died when he was run over at the age of 4; Glen still suffers flashbacks from pulling him out from under the car.

Zak, an academically bright child, enrolled at a local junior school and excelled in his first six months at the Villa academy. A pivotal problem arose when he set up a goal with a look-away pass during a training match. The coach stopped the session, criticised the extravagance of the gesture, and alienated the child.

‘Zak, being a nine-year-old, took that as a personal jibe. It wasn’t, because we saw other kids get the same treatment, but they were looking for conventional play. Pick up, pass, look to receive. I didn’t think there were too many better than him at running with the ball, and being tricky, so I worried they would take away what was good about him.

‘Was he going to be another statistic, and fall away? I realise, even as I say that, I was lost in the process of how he was going to get through. Zak started to feel his coaches were on at him. I was instructing him another way, saying, “Don’t let your skills go. It’s about bums on seats in this game.”

‘I’ve changed, thank God, but I’m just trying to be candid. I don’t like a lot of what I see in myself back then. It’s very difficult for a nine-year-old to do what his dad is asking, when people at the club are saying, “Don’t do this, don’t do that.” In the end he said, “Dad, I am not sure I want to do this any more.”

‘We did have more time together as an immediate family because of the relocation, but we missed the respite care we received from our extended family. We didn’t realise how much they did for us, minding the boys at the weekend. I started suffering from anxiety. Me and Rachel started, you know, falling apart a little bit. I felt I should know what to do, but I didn’t. I just didn’t.

‘When we went to see the club, to talk about the way Zak was being treated, we were just sort of palmed off, when we were welcomed with open arms before. It became a real tug of war. I was told, “You need to show more commitment.” So I’m like, well, you’ve not suggested we move down, but I’ve relocated my family …’

The decision to leave, exacerbated by a dispute over mileage expenses, was complicated by a far-reaching disagreement over the nature of Zak’s contract. The club rejected his father’s contention he had been promised his son would be released without compensation; the boy was unable to play for ten months while Villa sought a fee.

Manchester City eventually recruited him, on the recommendation of Sheffield-based Kristian Wilson, one of their elite development coaches. His registration was initially rejected by the Premier League, because the family lived outside prevailing one-hour travel time limits due to a difficult journey across the Peak District, but accepted the Brunts’ counter-argument on appeal that relocation was impractical because of the twins’ need to be within reach of hospital treatment.

City were welcoming. Zak was invited to meet Roberto Mancini in the dugout before a league game, ironically against Villa. He met Joe Hart and was presented with David Silva’s signed shirt. Yet his form in his first season, in the under-11s, was lukewarm. His problems during the second season were compacted by the disintegration of his father’s relationship with a co-ordinating coach for the under-12s and -13s.

A confrontation, triggered by disputed accusations of favouritism and a perceived lack of game time, marked a point of no return. Glen admits he sent City an anonymous letter of complaint, which was not acted upon. He was left to pick up the pieces when the club acceded to his request that Zak should be released.

‘Don’t get me wrong. There are some good people at City, but Zak’s self-esteem suffered. He doesn’t stay low for very long, because he has an intrinsic ability to bounce back, but that doesn’t make it right. He was known in Chesterfield as the kid that plays for Man City. All of a sudden he’s the kid playing grassroots football. There were snide remarks towards him. He found it difficult.’

A YouTube clip of him as an 8-year-old in a red England kit, demonstrating his ball skills, was used against him. An ill-advised caption read: ‘Remember his name. This boy is going to be a star.’ Innocence acts as incitement on what should really be termed anti-social media; commentaries were crass, callous and barely literate:

It’s one thing kicking a ball around in your back garden. I’m pretty sure he won’t have the time to be doing pointless tricks in the middle of a game …

A lot of kids his age are better. For all we know, them videos could have took hundreds of takes before any of them worked …

I see all these videos of kids having mad skill and that there the next Messi or Ronaldo but in reality there probably gonna suck …

Even someone like me, inured to the rough and tumble of opinion over decades observing sport at the highest level, treads warily in the comments section, beneath the line. Such forums offer a platform for cowards

and charlatans, the deluded and the plain nasty. Experience would have cautioned Zak against plunging into the cesspit, but his strength of character, in directly answering his detractors, was admirable.

This boy is crap he isn’t going to make it to pro won’t even come close …

Thank you very much for your support I will use it to drive me.

It’s so annoying when he finishes doing his skill and he just stays there staring at the camera happily.

You got a problem with me being happy? I’m sure last time I checked football was a hobby in which your supposed to enjoy yourself.

Kid kill Your Self for once u know im better boi whitey im asian boiiiii you look like a burnt white sweet potatoe with your crocodile HAIR

Thank you very much for your comment I appreciate it …

This, remember, is a boy approaching his twelfth birthday, a blood sacrifice on the altar of so-called public opinion. Zak stayed at home, watching videos of Paul Gascoigne and falling in love with South American football. The sense of a family being sucked into a vortex of unfeasible ambition heightened when he announced he would like to study at a Brazilian academy. Even now, more than two years later, Glen shakes his head at the surreal nature of the subsequent conversation:

‘I said, “You know where Brazil is. That’s obviously not going to happen.” So he said, “Where’s the second best place in the world to learn, then?” It has to be Spain, doesn’t it? My wife is as barking mad as I am, and she is privy to this, so she just said, “Take him.” I said, “What do you mean, take him?” She said, “Just take him. You don’t want to go into another English academy, do you?”’

No Hunger In Paradise

No Hunger In Paradise The Nowhere Men: The Unknown Story of Football's True Talent Spotters

The Nowhere Men: The Unknown Story of Football's True Talent Spotters